Francisca Niklitschek

Autores contribuintes

Dmitrij Achelrod Doutoramento

Francisca Niklitschek

Lembra-se da primeira vez que falámos sobre o nosso sistema nervoso? Imaginámos-no como um arquiteto invisível, o centro de comando principal que orquestra tudo, desde um simples piscar de olhos até aos nossos pensamentos mais complexos. Aprendemos que esta rede intricada não é apenas um sistema, mas um belo e dinâmico dueto entre o “go” do Sistema Nervoso Simpático (SNS) e o “slow” do Sistema Nervoso Parassimpático (PNS).

O SNS, o acelerador do nosso corpo, evoluiu para nos ajudar a lidar com ameaças: a clássica resposta de “lutar ou fugir”. O PNS, por outro lado, é o pedal do travão do nosso corpo, concebido para “descansar e digerir”. Mas, como descobrimos, a vida moderna tem uma forma trágica de manter o acelerador pressionado. Somos constantemente bombardeados pelos “tigres dente-de-sabre” dos prazos, alertas e informações avassaladoras, deixando o nosso sistema nervoso preso num estado de stress crónico. Este excesso constante, como vimos na nossa última publicação, pode afetar profundamente a nossa saúde física e emocional, desde problemas intestinais até ansiedade.

Então, como podemos começar a travar e encontrar o caminho de volta ao equilíbrio? A resposta tem menos a ver com tecnologia complexa e mais com lembrar as nossas raízes. Trata-se de nos reconectarmos com o nosso co-regulador original: a natureza.

Há uma razão pela qual um passeio por uma floresta tranquila parece um remédio, mesmo quando não se consegue explicar porquê. Não é apenas o ar fresco ou a forma como a luz do sol dança através das folhas. É algo ligado à própria arquitetura do nosso sistema nervoso, uma profunda ressonância com o mundo natural que o nosso corpo recorda.

O nosso plano evolutivo

Durante centenas de milhares de anos, os nossos corpos evoluíram em constante diálogo com o mundo natural. O nosso sistema nervoso foi moldado pelo ritmo constante da luz do dia e do anoitecer, pelo sussurro das folhas agitadas pelo vento e pela presença tranquila das árvores. Nesses espaços, os nossos corpos aprenderam o que era a sensação de segurança. O farfalhar das folhas podia sinalizar uma ameaça potencial, ativando o nosso SNS. Mas os padrões constantes e previsíveis da natureza, o bater rítmico das ondas, o lento arco do sol, diziam aos nossos corpos quando era seguro baixar a guarda e deixar o PNS assumir o controlo. [1],[2],[3].

Este design evolutivo explica por que a vida moderna pode parecer tão exaustiva. Os nossos sentidos são bombardeados por ecrãs, ruídos e urgências. No entanto, quando saímos e deixamos o nosso sistema nervoso descansar no ritmo mais lento da natureza, algo notável acontece: a nossa fisiologia muda. O nosso corpo reconhece esses sinais naturais como familiares, seguros e reconfortantes, porque fazem parte do nosso projeto biológico.

Mecanismos da natureza: como o seu corpo reage

Então, o que exatamente acontece quando mergulhamos na natureza? É uma conversa mágica, comprovada pela ciência, entre os nossos sentidos e o nosso sistema nervoso:

- Estimulação sensorial e ativação parassimpática: quando observamos cenas naturais, como uma floresta verdejante ou um corpo de água calmo, o nosso cérebro processa essas imagens de maneira diferente. Em vez do foco de alta intensidade exigido pelos ambientes urbanos, a nossa atenção pode vagar suavemente. Esse “fascínio suave” acalma a mente e ativa o SNP, diminuindo a frequência cardíaca e melhorando a nossa capacidade de recuperar do stress. Sinais auditivos, como o canto dos pássaros ou uma brisa suave, também atenuam a resposta de “luta ou fuga”. [4],[5].

- Modulação hormonal e neuroquímica: Entrar em contato com a natureza reduz a liberação de hormônios do stress, como o cortisol e a adrenalina. Ao mesmo tempo, aumenta a produção de endorfinas e serotonina, que influenciam o nosso humor e a nossa sensação de bem-estar. Trata-se de uma conversa direta entre o nosso sistema nervoso e o nosso sistema endócrino, ajudando a equilibrar a resposta ao stress. [4],[5].

- Melhoria da variabilidade da frequência cardíaca (VFC): Como aprendemos na nossa publicação anterior, um sistema nervoso flexível é um sistema saudável. Quando estamos na natureza, a nossa variabilidade da frequência cardíaca (VFC) muda para padrões que indicam que o nosso SNP está no controlo. Esse aumento da flexibilidade autonómica é um sinal de que o nosso corpo está mais apto a adaptar-se aos desafios e a recuperar deles. [6],[7].

Mecanismo | Efeito-chave | Benefício de apoio |

Estímulos sensoriais (por exemplo, imagens, sons) | Aumenta o tónus vagal, diminui a atividade simpática | Redução rápida do stress, melhora do humor |

Alterações hormonais (por exemplo, diminuição do cortisol) | Equilibra as hormonas com apoio vagal | Maior resiliência ao stress crónico |

Melhoria da VFC | Promove flexibilidade autonómica | Melhor regulação emocional e recuperação |

Sinais evolutivos de segurança | Ativa circuitos neurais restauradores | Redução da ansiedade, conexão social |

Encontrando a sua calma interior: as ferramentas da natureza

Não precisa desaparecer na selva para sentir o toque calmante da natureza. O nosso sistema nervoso pode responder até mesmo às menores doses. Pense nisso como uma microdosagem da natureza:

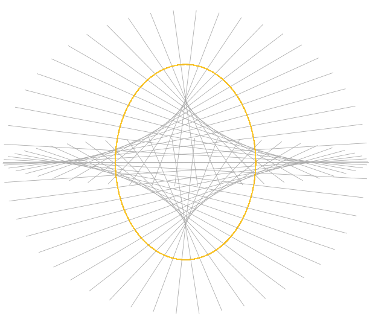

- Árvores e espaços verdes: Reserve um momento para observar atentamente os galhos de uma árvore. Os padrões geométricos repetitivos, conhecidos como fractais, têm um efeito calmante mensurável no nosso cérebro. [8]. Os nossos sistemas visuais evoluíram com essas formas, por isso elas parecem inerentemente familiares e seguras. Além disso, simplesmente ser entre as árvores expõe-nos a compostos derivados de plantas chamados fitoncidas, que podem ativar respostas de relaxamento no nosso sistema nervoso. Esta é a ciência por trás do “banho de floresta” (shinrin-yoku). [9].

- Sons da água e silêncio: Os nossos ouvidos estão sintonizados para encontrar segurança em certas paisagens sonoras. O bater rítmico das ondas do mar ou o fluxo constante de um rio sinalizam previsibilidade e calma. Esta é uma forma de co-regulação auditiva. O silêncio texturizado da natureza, a pausa entre o canto dos pássaros, a quietude após o vento, também dá ao nosso sistema nervoso uma oportunidade muito necessária para se acalmar e diminuir o ritmo da vigilância.

- Luz solar e ritmo circadiano: os nossos corpos são máquinas sensíveis à luz, e a luz natural é crucial para regular o nosso relógio interno, ou ritmo circadiano. [10]. A luz da manhã sinaliza ao nosso corpo para acordar e se energizar, enquanto a luz dourada do entardecer nos prepara para o descanso. Passar algum tempo ao ar livre, mesmo que seja por alguns minutos, ajuda a realinhar esses ritmos e restaurar uma sensação de vitalidade que é essencial para um sistema nervoso regulado.

O mais bonito é que esses benefícios são ampliados quando os partilhamos. Dar um passeio com um amigo, sentar-se tranquilamente com entes queridos debaixo de uma árvore ou até mesmo partilhar um momento de silêncio ao ar livre pode aprofundar os sentimentos de segurança e pertencimento. Os nossos sistemas nervosos co-regulam-se não apenas com o ambiente, mas também entre si, reforçando a confiança e a conexão.

O convite: volte para casa, para os seus ritmos

De muitas maneiras, regular o nosso sistema nervoso não significa aprender algo novo, mas sim lembrar-nos do que já sabemos. Os nossos corpos, por baixo das camadas de ruído urbano e luz digital, ainda carregam a memória ancestral de viver em sincronia com os ritmos da Terra. Reestruturar os nossos sentidos significa dar a nós próprios permissão para sentir o vento na nossa pele, para ouvir o silêncio entre os sons e para observar o lento arco do sol. Trata-se de deixar a nossa respiração acompanhar o ritmo das árvores.

Assim como cuidamos da nossa higiene diária, podemos cuidar do nosso equilíbrio interior, integrando a natureza nas nossas rotinas. Esses pequenos atos consistentes recalibram os nossos sistemas em direção à segurança, conexão e vitalidade. O convite é simples: volte para casa, para os ritmos que sempre foram seus.

Bibliografia

[1] U. Hasson, S. A. Nastase e A. Goldstein, ‘Direct Fit to Nature: An Evolutionary Perspective on Biological and Artificial Neural Networks’ (Adequação direta à natureza: uma perspetiva evolutiva sobre redes neurais biológicas e artificiais), Neuron, vol. 105, n.º 3, pp. 416–434, fevereiro de 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.12.002.

[2] L. E. Egner, S. Sütterlin e G. Calogiuri, ‘Propondo uma estrutura para os efeitos restauradores da natureza através do condicionamento: Teoria da Restauração Condicionada’, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health, vol. 17, n.º 18, p. 6792, janeiro de 2020, doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186792.

[3] S. W. Porges, ‘Orientando-se num mundo defensivo: modificações mamíferas da nossa herança evolutiva. Uma Teoria Polivagal’, Psicofisiologia, vol. 32, n.º 4, pp. 301–318, julho de 1995, doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb01213.x.

[4] V. F. Gladwell et al., ‘Os efeitos das vistas da natureza no controlo autónomo’, Eur. J. Appl. Physiol., vol. 112, n.º 9, pp. 3379–3386, setembro de 2012, doi: 10.1007/s00421-012-2318-8.

[5] D. K. Brown, J. L. Barton e V. F. Gladwell, ‘Ver cenas da natureza afeta positivamente a recuperação da função autónoma após stress mental agudo’, Environ. Sci. Technol., vol. 47, n.º 11, pp. 5562–5569, junho de 2013, doi: 10.1021/es305019p.

[6] T. Mizumoto et al., ‘Efeitos fisiológicos da visualização de imagens do ambiente natural na variabilidade da frequência cardíaca em indivíduos com transtornos depressivos e de ansiedade’, Sci. Rep., vol. 15, n.º 1, p. 16317, maio de 2025, doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-00681-4.

[7] E. E. Scott et al., ‘O sistema nervoso autónomo no seu ambiente natural: a imersão na natureza está associada a alterações na frequência cardíaca e na variabilidade da frequência cardíaca’, Psychophysiology, vol. 58, n.º 4, p. e13698, 2021, doi: 10.1111/psyp.13698.

[8] C. M. Hagerhall, T. Laike, R. P. Taylor, M. Küller, R. Küller e T. P. Martin, ‘Investigations of Human EEG Response to Viewing Fractal Patterns’ (Investigações sobre a resposta do EEG humano à visualização de padrões fractais), Perception, vol. 37, n.º 10, pp. 1488–1494, outubro de 2008, doi: 10.1068/p5918.

[9] ‘Shinrin-yoku’, Wikipedia. 29 de junho de 2025. Acedido em: 14 de agosto de 2025. [Online]. Disponível: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Shinrin-yoku&oldid=1297901131

[10] ‘Ritmo circadiano’, Wikipédia. 3 de agosto de 2025. Acedido em: 14 de agosto de 2025. [Online]. Disponível: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Circadian_rhythm&oldid=1304065871

Patrick Liebl,

Facilitador principal e especialista em integração

Tens curiosidade em saber mais?

Convidamos-te a marcar uma chamada connosco. Juntos, podemos explorar quaisquer questões que possas ter. Podemos explorar se um programa com uma experiência psicadélica legal é adequado para ti neste momento.

"Estamos aqui para apoiar a tua exploração, ao teu ritmo, sem expectativas." - Patrick Liebl