The "Psychedelic" Name Game:

Shaping Perception and Experience

Chapter 2: What are Psychedelics?

Estimated reading time: 9 min

April 11, 2023

Journey into Chapter 2: What are psychedelics?

In the first article of this series “Psychedelics 101”, we explored how psychedelics have been used for thousands of years by various cultures to induce visionary experiences and explore the depths of consciousness. We also touched on how the renaissance of scientific research into psychedelics unveils the great potential of treating mental health conditions in innovative ways. This has led to more and more people paying attention to this movement as it makes its way into the mainstream. People are increasingly eager to experience the benefits of these powerful compounds themselves.

Now enter Chapter 2. We will explore the most important topics that will deepen your understanding of what psychedelics really are. Using scientific research results to poetic expression, metaphors, and artistic imagery Chapter 2 of the Psychedelics 101 series covers:

- The “Psychedelic” Name Game

- Psychedelics in Medicine: A Western Categorization

- Redefining the drug spectrum: psychedelics, cannabis & “hard drugs”

- Seeing beyond the Western perspective.

- Inside the Psychedelic Mind

- The Precarious Edge of Psychedelic Transformation: the “bad trip” paradox

The “Psychedelic” Name Game

Why are psychedelics called psychedelics & how does that influence the experience?

Psychedelics are a group of substances that reliably induce a remarkable and drastic shift in subjective experience. The origin of the term “psychedelics” stems from the Greek words “psykhē”, meaning “mind, soul or intelligence” & “dēloun”, which translates to “manifest or reveal”.

Psychiatrist and psychonaut Dr. Stanislav Grof, who has led thousands of LSD-assisted psychotherapy sessions, writes about psychedelics:

LSD and other psychedelics function more or less as nonspecific catalysts and amplifiers of the psyche.

This is reflected in the name given by Humphrey Osmond to this group of substances; the Greek word “psychedelic” translates literally as mind-manifesting.

Understanding psychedelics as “mind-revealing” substances is a useful guiding star for us as captains to navigate our ship towards fathoming the nature and meaning of the vast sea of these experiences in altered states of consciousness.

“The idea is that our ordinary conception of reality, what we experience in our daily lives, draws on only a restricted capacity of our minds—that we are capable of entering other states of awareness which show reality to be infinitely more vast and complex than we ordinarily know.”

– Stanislav Grof

Hallucinogens, psychotomimetics or teonanácatl?

Before psychiatrist Humphrey Osmond coined the term “psychedelics” for these substances in a letter to his friend Aldous Huxley in 1957, they have gone by a variety of names [1]. Unsurprising, given the breadth of experiences that these substances can induce and the different cultural contexts in which those names arose. Even within the Western world the nature and potential of these substances were understood in different ways in the past decades. The varying terms used to refer to these substances reflect that evolution.

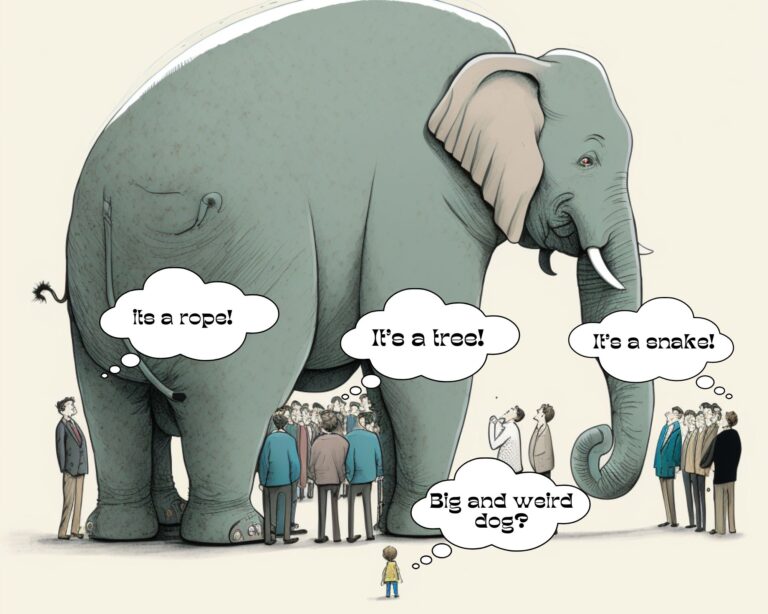

Consider the last four lines in ‘’The Blind Men and the Elephant’’, a poem by John Godfrey Saxe based on an old folk tale from India.

Each in his own opinion

Exceeding stiff and strong,

Though each was partly in the right,

And all were in the wrong!

It illustrates how each perspective is only able to grasp a portion of the whole truth. By exploring multiple perspectives, a synthesized and inclusive understanding of what psychedelics really are can be formed.

Throughout time, botany anthropologists, chemists, psychiatrists, philosophers, and shamans have developed their unique perspectives on what psychedelics are.

These substances have been called “Hallucinogens” by skeptics and scientific materialists, recognizing the potential of experiencing phenomena that are not present in ordinary states of consciousness, ranging from subtle changes in the visual field to encounters with “other beings”.

They have been referred to as “Psychotomimetics”, a popular term in early Western clinical research into these substances starting in the 1950s [2]. It reflects that the states psychedelics induce were considered to be similar to (temporary) psychotic states like in schizophrenia.

Many indigenous cultures share the view of psychedelics being sacred plants. The Mazatec culture referred to their sacred mushrooms as “teonanácatl” or “flesh of the gods”. “Vine of the soul” is the translation for the psychedelic brew ayahuasca that was used in ceremonies to connect with the plant to heal psychologically and physically and explore the nature of reality. The view of sacred plants aligns with the term Entheogen [3] that later emerged in the West, meaning “generating the divine within”. It points to the possibility of a mystical experience when under the influence of a psychedelic, frequently characterized by “ego-dissolution” and a feeling of “unity” with the cosmos.

The term “Psychedelics” provides a more neutral and holistic frame as it takes a step back and looks at the whole elephant, or at least, it is more inclusive of its parts as it allows for the possibility of varying experiences being induced. The key feature of that term is that psychedelics interact with the conscious and unconscious mind, creating a complex and unpredictable experience.

Change the way you look at things and the things you look at change.

– Dr. Wayne Dyer

What’s interesting about psychedelics is that the way we understand them highly influences the psychedelic experience. Yes, that’s right, the way you look at things changes the way things are.

The framing and perception of the experiencer and his or her guide or facilitator create the context or “set” in which the experience takes place. Even the way that people who are present and interact with the experiencer before, during, and after their experience have an influence on the experience. This framing and perception include expectations and openness, the way of interpreting the experience, the quality of support during the experience, and the physical environment.

Clinical psychiatrist Rick Strassman illustrates that point in his book “The Psychedelic Handbook” with the following hypothetical example:

Picture a study where participants are exposed to a psychedelic experience, both the participants and the researchers think of psychedelics as substances that induce psychotic states. The researchers ask the participant to fill out a “schizophrenia rating scale” after the experience.

In another study, the participants are given the same substance. However, this time, the researchers called it an “entheogen” or “God-revealing” substance. Staff treat the participant with compassion, respect and was therefore primed to be open to a spiritual experience. To evaluate the experience, the participant filled in a “spiritual experience rating scale”.

Strassman concludes saying that it is not difficult to see how different such experiences will be with the same drug and the same individual due to the strinkingly different contexts.

Our views on psychedelics are not the only factor that shapes the experience. Research and ancient traditions have come to understand a handful of important principles to steer and guide these experiences, allowing for the use of these consciousness technologies and an exploration of our minds in a grounded, safe, life-affirming and purpose-oriented way. Later, in Chapter 4 of this Psychedelics 101 series, we will explore these principles.

How does Western Medicine view Psychedelics?

The next article of this chapter, “Psychedelics in Medicine: A Western Categorization” is a dive into the Western medical categorization of psychedelic substances.

Images

Uncited images were created by Nino Galvez using AI image generators

References:

[1] Nichols, D. E. (2016, April). Psychedelics. Pharmacological reviews. Retrieved April 11, 2023, from this site.

[2] WERKMAN, S. I. D. N. E. Y. L. (n.d.). The individual psychology of Alfred Adler | American Journal of Psychiatry. Retrieved April 11, 2023, from this site.

[3] Ruck, C. A., Bigwood, J., Staples, D., Ott, J., & Wasson, R. G. (1979). Entheogens. Journal of Psychedelic Drugs, 11(1–2), 145–146. doi:10.1080/02791072.1979.10472098

Subscribe to the insights newsletter

At most, once every 2 weeks.