Dmitrij Achelrod PhD

Dmitrij Achelrod PhD

Meditation, arguably the most important practice of Buddhism, has been regarded for millennia as a way to spiritual unfolding and awakening. Honed by spiritual teachers who dedicated their lives to this path and passed down over hundreds of generations to a chosen few, the Buddhist-inspired meditation practices in all their different forms and shapes have nowadays turned into a modern “institution” of spirituality, self-exploration and healing. Meditations on mindfulness, metta, loving kindness or transcendence have become mainstream, almost the new spirituality of the non-religious. Meditation masters’ reports about states of oneness, pure bliss or emptiness have fascinated myriads of seekers in the East and West. At the same time, the psychedelic renaissance has introduced magic mushrooms, ayahuasca and other psychoactive substances as the new cool kids in the spiritual block. Many people who have tried psychedelics claim that they could deepen their spiritual practice through them.

However, the Buddhist philosophy, oftentimes marked by its unapologetic requirements for discipline, self-control, and asceticism, to many followers seems antithetical to “tripping on psychedelics”. How could intoxicating drugs, anyway, be beneficial to reaching clarity of mind or honoring self-restraint?

Well, the relationship between psychedelics and Buddhist meditation calls for a more nuanced analysis. Certainly, psychedelics and Buddhism have had a partially conflicted, fuzzy relationship. But what if psychedelics and the inception of Buddhism itself went hand in hand? What if there were substantial historical, cultural, and spiritual intersections between the directional use of psychedelic substances and Buddhist practices? What if psychedelics could make you a better Buddhist (and meditator)? And what if Buddhism could make you a better psychonaut?

1. The fifth precept of Buddhism: you shall not take…psychedelics?

The path of Buddhism basically teaches how to achieve liberation of the mind. One of the preconditions for this is living a moral life (called “sīla”). Sīla, the path of morality, lays the necessary groundwork for evolving our meditation practice. We cannot be living the life of a villain, killing people and stealing, and be thinking that spending a few hours a day on the meditation cushion will bring redemption. The Buddha taught that Right Action, Right Speech and Right Livelihood thus have to go hand in hand with meditation. Particularly, the Buddha invites us to follow and train five moral precepts or virtues (pañca-sīla, according to the Theravada tradition):

- Refrain from killing living beings

- Refrain from stealing

- Refrain from sexual misconduct

- Refrain from false or malicious speech

- Refrain from using intoxicants and drugs

So what did the Buddhist scriptures refer to when they urged their followers not to intoxicate themselves? And why?

Basically, the scriptures refer to all sorts of intoxicants that might induce heedlessness or clouding of the mind. They do not specifically mention concrete substances. However, depending on the Buddhist tradition, the fifth precept is interpreted to include alcohol, psychoactive substances that lead to altered states of consciousness (that would include psilocybin mushrooms), and also more common substances like tobacco and caffeine. Above all, there is one essential reason that motivates the prohibition of intoxicants: the preservation of mindfulness. Buddhism places great emphasis on mindfulness (sati) and clarity of mind. Intoxicants are believed to cloud the mind, impede judgment, and hinder the ability to maintain awareness of one’s thoughts, actions, and motivations. Drugs can impair one’s ability to make wise decisions, leading to harmful actions that go against the principles of all other four precepts. We all have heard stories of drunk or drugged people committing petty crimes or felonies – the fifth precept seems pretty reasonable and justified. In conclusion, intoxicants are seen as obstacles to our spiritual development because they create mental obscuration and can seduce us to act against the other precepts.

2. Scratching the surface: The best-kept secret of Buddhism

In recent years, different authors have been investigating the seemingly clear stance that Buddhism has towards drugs and intoxicants. What they found when scouring ancient texts might surprise most people, and particularly the hard-liners that defend categorical abstinence.

In his fascinating Book “Secret Drugs of Buddhism”, Crowley marshals astounding pieces of evidence showcasing how psychoactive substances most likely have played a foundational role in the rise of Buddhism.[1] Over many centuries, Tibetan Buddhists have developed a vast panoply of psychopharmacology and have worked with a sheer endless number of psychiatric botanical medicines—none of which have ever been previously identified or scientifically tested in the West. One example, probably the most salient, is the secret potion of “amrita”. The most ancient Tibetan commentary on Vajrayana Buddhism defined seven levels of secrecy – and the nature of this wondrous potion is level seven. Probably the best hidden secret of Buddhism. Crowley posits that amrita, a highly potent psychoactive concoction, was central to ancient rituals of Vajrayāna Buddhism, indicating a direct historical link between the use of mind-altering substances and Buddhist practice. Amrita was mentioned in the scriptures as the “elixir of immortality.” Just a single drop of amrita would make us “pure and immortal, possessed of the five eternal wisdoms” and help attain “the highest enlightenment”.[2]

In the Vedas, amrita was used as a synonym for “soma”, in mythological terms the mysterious potion that made the gods immortal. Crowley’s detailed accounts leave little doubt that in early Vajrayana Buddhism, the psychoactive amrita was consumed as the sacramental drink at the beginning of all major rituals. Amrita and other psychoactive substances also found their way into Buddhist symbolism.

Some of the most revered Indian deities originated as manifestations of psychedelic plants (and Buddhism adapted many deities from Hinduism).

For instance, Śiva (later adapted as Avalokiteśvara in Buddhism), who has one leg and a blue throat, was very likely the apotheosis of a Psilocybe mushroom, which characteristically turns blue when picked.[1]

Similarly, Vajrayoginī, one of the Vajrayāna’s most important meditation deities, has numerous symbolic allusions to Amanita muscaria (known as the fly agaric mushroom). Oftentimes, Vajrayoginī is portrayed standing on one leg and has the characteristic red color with white ornaments. Her necklace of dried heads might be symbols for the dried heads of Amanita muscaria.

In conclusion, many of the earliest Buddhist practices, including initiation rituals, relied on psychedelic drugs. Bharati concludes that “There cannot be the slightest doubt that the Hindus and probably the Buddhists of earlier days did regard the taking of psychedelic drugs as part of the wide range of sādhanas which lead to ecstasy”[4]

3. The rise of Buddhism in the West – elevated by psychedelics?

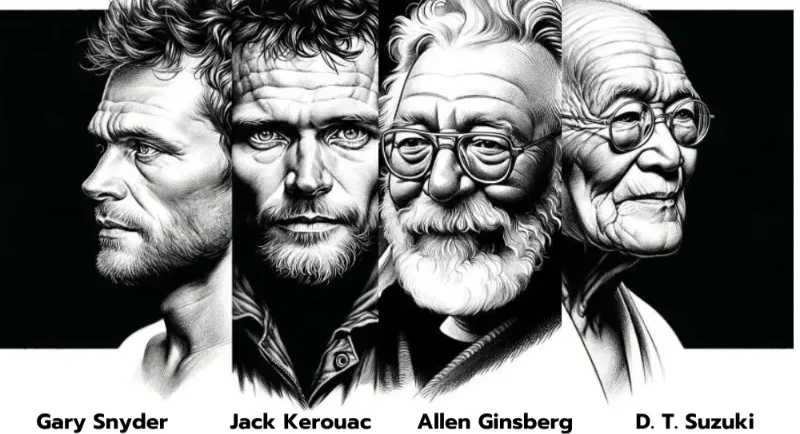

Interestingly enough, the connection between psychedelics and Buddhism was revived again in the West. The interest in Buddhism in the West started burgeoning in the mid-20th century. After World War II, there was a significant cultural and spiritual shift, with many seeking alternative paths to meaning and enlightenment. In the 1950s and 1960s, figures from the Beat Generation were instrumental in popularizing both Buddhism. Often considered the figurehead of the Beat Generation, Kerouac’s works like “On the Road” and “The Dharma Bums” were pivotal in bringing Buddhist concepts to a broader American audience. His writings reflected a personal journey through Buddhism, especially Zen, blending it with a bohemian lifestyle. Gary Snyder, a poet, environmental activist and another central figure in the Beat movement, was deeply influenced by Zen Buddhism. He spent significant time in Japan studying Zen and brought back a rich understanding of Buddhist philosophy, which he infused into his poetry and essays.

More and more writings were translated from Sanskrit or Japanese into English, for instance by D.T. Suzuki, which led to a rapid proliferation of Buddhism and a mushrooming of Buddhist centers around the USA.

While most Buddhist teachers today seem to disparage psychedelics as a legitimate instrument for inner exploration and spiritual growth, it was no secret though that these Western thought-leaders of Buddhism were also avid psychonauts in their early days. For example, Ginsberg’s exploration of psychedelics was more than just well-documented, and he often drew parallels between his psychedelic experiences and Buddhist concepts. For many who later would turn into Buddihst teachers, psychedelics represented an important element in their explorations of consciousness. Jack Kornfield, one of the most respected teachers of Buddhism in the West, admitted about psychedelics: “They were certainly powerful for me. I took LSD and other psychedelics at Dartmouth after I started studying Eastern religion. They came hand-in-hand as they did for many people. It is also true for the majority of Western Buddhist teachers, that they used psychedelics at the start of their spiritual practice.”[5] In his book Zig Zag Zen, Baldiner illustrates in great detail how a number of Western philosophers and avant-gardists were influenced by psychedelics and turned to Buddhism for spiritual guidance.

So what made these psychedelic pioneers turn to Buddhism? And could psychedelics even help to walk the Buddhist path?

Psychedelic peak states can induce experiences that have a striking similarity with deep meditative states or Buddhist concepts of non-duality and interconnectedness. Thus, psychedelics can offer a truly experiential perspective on core Buddhist teachings. Many people that have had mystical experiences under the influence of psychedelics might be looking for a philosophical framework to embed these insights. Buddhism turned out to be one of them.

For instance, psychedelics might help experience “no-thing-ness” or “voidness” (śunyatā). On a deeper level, psychedelics can help us reveal the nature of mind itself. Buddhist teachers often use the analogy of a screen for the primordial mind. The pictures we see on the screen represent our streams of thoughts, emotions, feelings. Most of the time, and especially when we are not mindful, we only see the pictures or even merge with them. We think that the sequence of ever-changing pictures is the mind, that we are just the sum of our thoughts. We mistake the pictures for the screen. But in fact, the screen is always present. To see the screen, we need to take distance (or, in modern psychological terms, to diffuse) from the pictures. To become aware of the screen equates to ending our “ignorance” (or “not-seeing”, avidya, the source of suffering according to Buddhism). This is what Buddhist meditation practice is for. “Put into these terms”, Crowley explains, “to become enlightened is simply to notice the “screen.”” While psychedelics definitely do not guarantee “seeing the screen”, they might. Maybe just a glimpse at the screen, but this is still a stimulating foretaste.

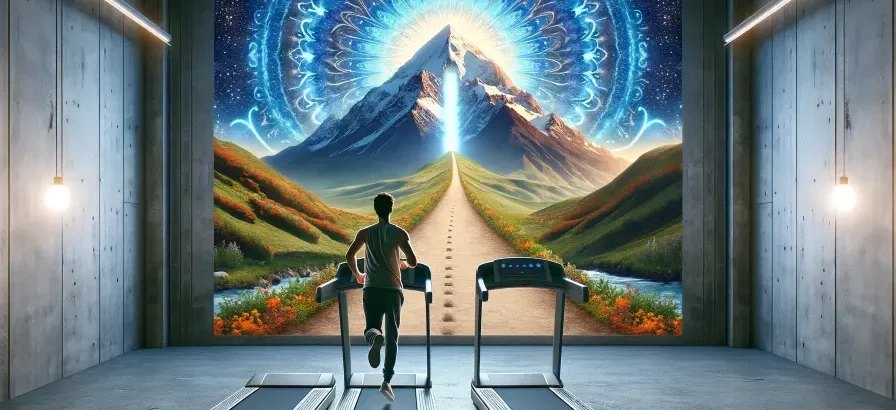

In a documentary on consciousness, the late Prof. Roland Griffiths from John Hopkins University said that “meditation is the tried and true course for understanding the human mind, and psilocybin is the crash course” (watch Aware here). If used under the right conditions, with an appropriate mindset and guidance, psychedelics might potentially accelerate the practitioner’s understanding of Buddhist principles and provide a gateway for deeper explorations of Buddhist concepts.

Similarly, both psychedelics and deep meditation practice can alter our ways of thinking and perceiving the world, moving from a traditionally separate, mechanistic and linear understanding of the world to a more interconnected and comprehensive awareness. Both practices can help us reach the conclusion that such a linear and reductionist perspective is subjective and constructed by humans, rather than an absolute representation of reality. Many if not most of psychonauts-turned-Buddhist-teachers in the West realized that such a holistic viewpoint isn’t exclusively achieved through psychedelics. It is actually a fundamental aspect of the Buddhist school of thought. Recognizing that psychedelics might be a powerful initiation, many started exploring and committing to the wisdom of Buddhism after their phase of intense psychedelic journeying.

4. Can Buddhism help us in our psychedelic journeys?

Is there a case to be made that Buddhist practices, in particular meditation, are useful for psychedelic work? Indeed, there is.

4.1 A Tibetan psychedelic guide

Already in the 60’s, psychedelic pioneers started uncovering the potential applications of ancient Buddhist practices for their psychedelic journeys. One such notable example is the Tibetan Book of the Dead, one of the first translations of a Tibetan scripture into English, which details a variety of visionary deities and Buddhas. Its original Tibetan title, Bardo T’ödol, translates to something akin to a “liberation through hearing in the transitional state between death and rebirth.” The text of Bardo T’ödol reveals that these divine figures might manifest during certain states of meditation and are believed to appear to individuals post-mortem. Importantly, the scripture advises practitioners to remain dispassionate and detached in the presence of these deities, whether they are serene or fierce, emphasizing that they are nothing but reflections of one’s own enlightened consciousness. Timothy Leary, a highly contentious Harvard professor and LSD advocate, found this text profoundly relevant to the psychedelic experience. Inspired by its teachings, he collaborated in writing a modern version, titled The Psychedelic Experience, specifically aimed at guiding users of psychedelics like LSD and psilocybin.

4.2 Presence, equanimity and acceptance

In particular, the Buddhist-inspired technique of not being entirely swallowed up by strong feelings, thoughts or memories helps to develop an attitude of equanimity and acceptance even towards difficult phases of the psychedelic experience.

Phenomena like ego-death or dissolution of the ego, which are reported to be a common effect of high-dose psychedelic trips, can be handled with more ease and less anxiety when regarded from a Buddhist perspective. We begin to see our identity and story more like pictures flickering over the screen, and less like an unshakeable truth we must defend until death. We find it easier to let these thoughts and pictures pass by, observe them dispassionately, so that we can eventually discover the screen (or the mind itself) on which they are projected onto.

These principles of “diffusion” and acceptance have nowadays become main tenets of psychedelic-assisted therapy (e.g. based on acceptance and commitment therapy [ACT]). The essential Buddihst practice of mindfulness meditation lets us rest in the present moment, being open to whatever arises in the psychedelic experience without being too deeply attached to it. It provides us the steadfastness to stay calm during the storm and not get carried away.

4.3 How meditation calms our bodies during psychedelic experiences

Besides the helpful metaphysical insights, Buddhist meditation practices can have very materialist, physiological effects. When we engage in meditation and focus, for instance, on our breathing for a few minutes, our breathing pattern tends to slow down eventually, in turn activating the parasympathetic nervous system. This parasympathetic activation is the physical antidote to the fight-or-flight response and helps us achieve lower levels of cortisol, blood pressure, pulse as well as lower perceived stress response. This can be particularly useful when we are going through difficult times in our psychedelic journey and even start completely losing orientation. Not surprisingly, if we practice meditation regularly, we can more easily reconnect with our breath during a psychedelic trip and use it as an anchor to find our way back to our body. In this state grounded in our body, we can go through tough phases more easily.

4.4 Cultivating a beginner’s mind – a Buddhist path for a deep psychedelic journey

In addition, another central element in Buddhist practice – the “beginner’s mind” – comes in very handy for psychedelic journeys. In Buddhism, the concept of “beginner’s mind” (Shoshin in Japanese) is a term derived from Zen Buddhism, particularly emphasized by Shunryu Suzuki in his book “Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind.” It refers to an attitude of openness, eagerness, and lack of preconceptions when studying a subject, even when studying at an advanced level, just as a beginner would. This concept can be incredibly beneficial in the context of a psychedelic journey for several reasons:

Openness to New Experiences: Just as a beginner’s mind in Buddhism is open and free from preconceived notions, approaching a psychedelic journey with this mindset can enhance the experience. It allows individuals to be more receptive to new insights and perspectives that psychedelics might offer .

Lack of Expectations: A beginner’s mind is devoid of expectations about what should happen, which is particularly valuable in a psychedelic journey. Psychedelics can produce unpredictable and varied experiences; thus, not having fixed expectations can help individuals navigate these experiences more fluidly.

Embracing Uncertainty: A beginner’s mind is comfortable with not knowing and uncertainty. In a psychedelic state, where experiences can be confusing or ambiguous, this acceptance of uncertainty can reduce anxiety and fear, allowing for a more profound exploration of the mind.

Sharpened Mindfulness: A beginner’s mind encourages a state of heightened awareness and mindfulness. In psychedelic experiences, being fully present and mindful can lead to deeper introspection and understanding, as well as a greater appreciation of the experience itself.

4.5 The Buddhist path helping us overcome the most difficult psychedelic experiences

But most importantly, the Buddhist path is not just a collection of practices that affect mind and body alike, it is a way of engaging with life. It encourages us to cultivate compassion for ourselves as well as for all beings, to open our hearts to the thousand joys and sorrows of this existence without being completely overwhelmed by them. Practicing to build a strong back and soft chest is essential to remain compassionate yet not break under the pressures of an aching heart. In her touching book on “Being with Dying”, Buddhist teacher Joan Halifax explains that “all too often our so-called strength comes from fear, not love; instead of having a strong back, many of us have a defended front shielding a weak spine. In other words, we walk around brittle and defensive, trying to conceal our lack of confidence. If we strengthen our backs, metaphorically speaking, and develop a spine that’s flexible but sturdy, then we can risk having a front that’s soft and open, representing choiceless compassion.” Having practice in being in the present in a compassionate yet anti-fragile way will especially pay off in a psychedelic journey. We might re-experience deep emotions such as grief, dread or shame when on psychedelics. Embracing traumatic memories or suppressed or disowned inner parts with a soft, compassionate heart and a strong, steadfast back is our unique chance to integrate our shadows and let light into the darkest chambers of our soul. It allows us to confront what we need to see, instead of fighting against it or running away. Only then can integration and healing ensue. There are few philosophies as conducive to inner work as Buddhism.

5 “Buddhelics” for walking our spiritual path

As we have seen, the roots of both ancient and modern Buddhist traditions are deeply intertwined with the deliberate and conscious use of psychedelics, be it with psilocybin mushrooms or other psychoactive plants. Psychedelics were a vital part of their ceremonies, practices, and rituals. We discussed how psychedelics can deepen the Buddhist path and, at the same time, that the synergy between Buddhism and psychedelics works in both ways. We elucidated how many Buddhist practices, in particular mindfulness meditation, can be of great help in deepening and integrating our psychedelic journeys.

5.1 Moving beyond stigma

Nonetheless, the seeming disconnect between psychedelics and Buddhism that many modern Buddhist teachers profess today might have more to do with the War on Drugs and its lasting damage on the public perception of psychedelics than with the actual potential of these substances. Probably, many Buddhist teachers turned away from psychedelics during that era in order to protect their image. Nobody wanted to become the literal enemy of the state. As a result, psychedelics were relegated into the underground. In recent years, however, psychedelics have changed their stained underground robes for white scientist-coats and that has surely also opened the door to a refreshed Buddhist discourse. In 2014, Robert Thurman, a US-American Buddhist teacher, explained to a crowd at Burning Man that “while we all have within the chemicals that allow us to experience insight, clarity and bliss, at a time of global crisis on so many levels, the careful use of entheogens to accelerate our progress may be a skillful means, and compatible with the practice of Dharma.”

5.2 Embracing instead of escaping

But the mainstream Buddhist stance is still highly critical of psychedelic use. Another reason why psychedelics have been shunned by many Buddhist practitioners is that they perceive psychedelic use as an escape from reality. Instead of facing the harsh reality of life, psychedelics allow us a temporary getaway into a cozy imaginary world. This frequent argument is based on the assumption that psychedelics are like other consciousness-contracting drugs (like cocaine, alcohol, heroine, fentanyl etc), anesthetizing our pain and numbing our ability to feel our agonies. We believe that psychedelics, if used in the right context, can lead to the exact opposite: they allow us to put the finger into the wound, to get intimate with our pain, to get a clearer picture on a sometimes uncomfortable reality. If you want to learn how to choose the right context for your psychedelic experience, click here. A psychedelic traveler who is serious about spiritual growth takes responsibility for her suffering, just like a virtuous Buddhist would. This has nothing to do with escapism.

5.3 Spiritual bypassing with psychedelics?

Furthermore, some Buddhist teachers warn that psychedelics can seduce us to spiritual shortcutting and even overwhelm us with the intensity of the experience – how does a person who has never had a clue of the spiritual path react when she suddenly claims to meet God or dissolves in the universe? The branches of a tree with too many low-hanging fruits are prone to break with the next gust of wind.[6]

We should take that warning seriously: Jack Kornfield argues that “a lot of people use psychedelics in mindless or misguided ways, without much understanding. The spiritual context gets lost. It’s like taking a synthetic mescaline pill and forgetting the two-hundred-mile desert walk and the months of prayer and purification the Huichols use to prepare for their peyote ceremony.”[5]

We at Evolute Institute believe this is certainly a valid point. Taking psychedelics mindlessly can be a shallow and superficial experience at best case and destabilizing and dangerous in the worst case – the more so do we highlight the importance of a safe psychological and physical environment where due preparations have been made and guidance is available. If the foundations are not strong on which we are standing, traveling on psychedelics might leave us shaky and confused. At the same time, spiritual bypassing is not only a phenomenon in psychedelic circles, it happens frequently in followers of the Buddhist path as well. Jack Kornfield wrote an entire book about it called “After the Ecstasy, the Laundry”, where he cautions us that the deepening of our spiritual path does not happen (only) in moments of divine bliss (i.e. in peak states), but in the daily joys and struggles of life.

5.4 The humble path of lifelong practice

Having said that, we believe that when used with care, preparation, wise guidance and the commitment and discipline for real personal change in the long run, psychedelics can be an extremely powerful tool for deepening one’s Buddhist practice, be it meditation or evolving one’s outlook on life. Certainly, taking psychedelics is by no way a guaranteed path to enlightenment – neither the intensity nor frequency of our psychedelic experiences will necessarily bestow us with clarity of mind, compassion and wisdom. Many people seem to mistake this truism and get lost in their colorful psychedelic visions, believing the peak states alone are already proof of their advanced personal evolution. But ego transcendence, and personal growth don’t stop with the psychedelic ceremony, they are lifelong processes that need to be practiced in the most ordinary moments of life: when having a difficult conversation with a colleague, when we are confronted with the loss of a loved one, or when cleaning the kitchen, again. It is through our relationship with the profane that we can appreciate the sacred. We have to commit to the lifelong path of deepening our loving-kindness and compassion, of walking through life with a soft chest and strong back. A systematic practice is necessary. While awakening can happen in a moment, it takes a lifetime to integrate and really live it. Only then can altered states that we experience on psychedelics (or during meditation) truly be transformed into altered traits.

If Buddhism teaches us one thing, it is to be open to what is and to leave our biases behind so that we can see reality and ourselves more clearly. In this sense, let us approach the careful use of psychedelics as part of a spiritual practice with openness of mind and heart. May we find out for ourselves if they help us penetrate deeper levels of consciousness, nurture love and compassion or if they are, for us personally, rather a distraction on our path to freedom of suffering and to enlightenment.

Korean Zen master Seungsahn was once asked his opinion about employing psychedelics to facilitate the quest for self-discovery. He replied: “Yes, there are special medicines, which, if taken with the proper attitude, can facilitate self-realization.” But he wouldn’t be a Zen master if he hadn’t added: “But if you have the proper attitude, you can take anything—take a walk, or a bath.”[5] 😉

Bibliography of Psychedelics, Buddhism and Meditation

[1] M. Crowley and A. Shulgin, Secret Drugs of Buddhism: Psychedelic Sacraments and the Origins of the Vajrayana, 2nd edition. Santa Fe London: Synergetic Press, 2019.

[2] M. Walter, ‘The Tantra “A Vessel of Bdud Rtsi”, A Bon Text’, 1986, Accessed: Nov. 27, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://www.dspace.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/227110

[3] C. Lenz et al., ‘Injury-Triggered Blueing Reactions of Psilocybe “Magic” Mushrooms’, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., vol. 59, no. 4, pp. 1450–1454, 2020, doi: 10.1002/anie.201910175.

[4] A. Bharati, The Tantric Tradition. Weiser Books, 1975.

[5] A. Badiner, A. Grey, and S. Batchelor, Zig Zag Zen: Buddhism and Psychedelics, New edition. Santa Fe, NM: Synergetic Press, 2015.

[6] J. K. Armstrong, ‘Psychedelic Insight – Lions Roar’. Accessed: Nov. 27, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.lionsroar.com/psychedelic-insight/

Patrick Liebl,

Lead Facilitator & Integration Expert

Curious to learn more?

We invite you to schedule a call with us. Together, we can explore any questions you may have. We can explore whether a program with a legal psychedelic experience is right for you at this time.

“We are here to support your exploration, at your pace, with no expectations.” – Patrick Liebl